Part 1 — The Claims and the Courtroom

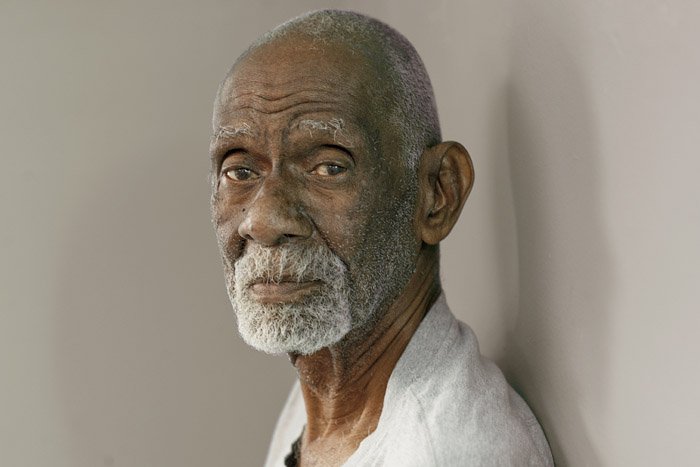

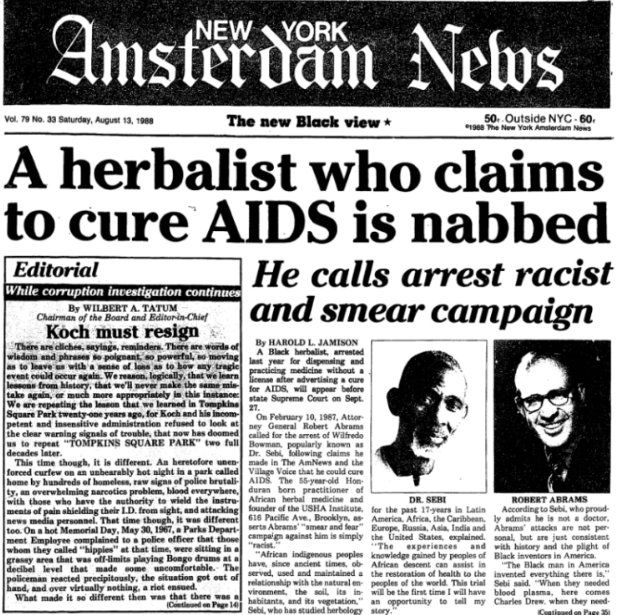

In New York during the late 1980s, Alfredo Darrington Bowman—known as Dr. Sebi—advertised herbal regimens and an alkaline diet he said could cure serious illnesses, including AIDS. His bold newspaper ads and public talks drew crowds—and the attention of state authorities. In 1987, prosecutors charged him with practicing medicine without a license, a crime under New York law when a person is said to diagnose or treat disease without proper credentials.

Accounts from the time say Sebi arrived to court with dozens of people willing to testify they’d been healed; numbers like “70” or “77” are often repeated in coverage and retellings. The state’s burden was to prove he made medical diagnoses; the jury acquitted him. Importantly, an acquittal meant the state failed to meet its burden—it did not constitute legal proof that Sebi’s methods cured AIDS.

Key sources: BET explainer; LA Times feature overviewing his claims.

Part 2 — The Civil Case & Consent Decree

Image via All That’s Interesting (reproduces New York Amsterdam News front page). Source: All That’s Interesting.

After the criminal acquittal, New York’s Attorney General pursued a civil consumer-fraud case focused on Sebi’s advertising claims. The matter concluded with a consent decree: he agreed not to make disease-curing claims in ads, to provide refunds, and to pay a modest fine (reported around $900). This wasn’t a criminal conviction; it was an agreement that curtailed future promotional claims.

For supporters, the criminal acquittal was vindication. For regulators and medical professionals, the civil decree reflected ongoing concerns about unsubstantiated claims around HIV/AIDS, a disease that—then and now—requires evidence-based treatment.

Cited background: Wikipedia summary of legal history; HRSA guide reflects standard of HIV care.

One of the absolute best medical holistic Black minds who was a threat to big medical profits worldwide”

Part 3 — Allegations of Pressure & the Racial Context

Many in Sebi’s community believe powerful pharmaceutical interests didn’t want any non-establishment cure circulating—especially one created by a Black man outside traditional institutions. This view surged back into the spotlight when Nipsey Hussle said he planned a Sebi documentary; after Hussle’s murder, conspiracy narratives multiplied online. Mainstream reporting has found no verifiable evidence that pharmaceutical companies directed the New York prosecutions; still, the narratives persist, fueled by a long, documented history of medical and governmental abuses against Black communities.

That history—Tuskegee, COINTELPRO, coerced sterilizations—makes skepticism understandable. But allegation is not evidence. As far as the public record shows, state actions centered on licensing and consumer protection, not industry capture.

Context on conspiracy surge and historical mistrust: GQ; AP News.

Part 4 — Outcomes: What Courts Did (and Didn’t) Decide

Summing up the record: (1) the 1987 criminal case ended in an acquittal on practicing-medicine-without-a-license charges; (2) a follow-on civil consumer-fraud action concluded with a consent decree restricting advertising claims and requiring refunds. No court held that Sebi “proved a cure for AIDS”; courts didn’t litigate clinical efficacy—they litigated licensing and advertising law.

Outside New York, media continued covering Sebi’s following and his later death in Honduras in 2016, circumstances that further fed speculation and legend-building around his life’s work.

Legal summary via Wikipedia; reporting on his death via Los Angeles Sentinel.

Part 5 — Legend vs. Evidence

Scientific consensus remains that there’s no credible evidence Sebi cured HIV/AIDS; effective HIV care relies on antiretroviral therapy. Still, the legend endures, powered by personal testimonies, cultural pride, and distrust of institutions—making Sebi one of the most polarizing figures in late-20th-century alternative health.

Whether you view him as visionary or as a promoter of dangerous claims, the courtroom record is narrow and specific. It did not certify cures; it stopped short of criminal liability and curbed advertising. The rest—the meaning of his work and its place in Black health history—belongs to culture, not the courts.

Editor’s note: Allegations about pharmaceutical interference are included here as claims circulating in the community; we did not find public documents tying any company to the prosecutions.